Legends of Pioneer Seattle

By Regina Scott

I grew up in the Seattle area, moving to the east side of Washington State to marry and raise my two sons. Now I'm back in the south Puget Sound and reacquainting myself with the stories of the early days for my Frontier Bachelors series. Washington State boasts some interesting real-life characters that I know you’ll love. I'll be expanding this article as I continue researching.

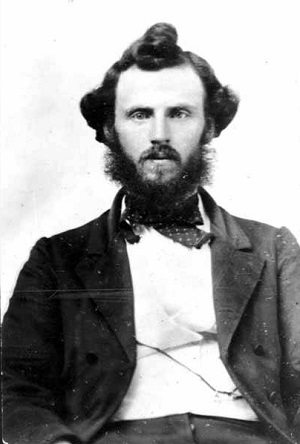

Asa Mercer and His Belles

Newspaper editor Horace Greeley has been credited with at least popularizing the phrase, “Go West, young man,” a mantra that led a generation of gentlemen to cross the mountains to the other side of the country. But it was an enterprising young man from Seattle who first conceived of the idea of bringing young women west in large numbers to marry bachelors and help settle the frontier.

Asa Shinn Mercer was a young college graduate Illinois. He had traveled west to join his brother, Thomas, in the fledgling Seattle. He helped build the territorial university (now the University of Washington), then stayed on at its first president and only instructor. It would have been a fine, respectable position for a young man, but for two things: he had only one student old enough to actually graduate any time soon, and too few prospects for more.

Asa Shinn Mercer was a young college graduate Illinois. He had traveled west to join his brother, Thomas, in the fledgling Seattle. He helped build the territorial university (now the University of Washington), then stayed on at its first president and only instructor. It would have been a fine, respectable position for a young man, but for two things: he had only one student old enough to actually graduate any time soon, and too few prospects for more.

You see, following the Civil War, men outnumbered women in Washington Territory by nearly nine to one. There are stories about men paying young fathers for the rights to marry a baby daughter, once she reached marriageable age. With women at such a premium, Mercer could see his vision of a prosperous future dimming. So, he conceived of another vision. The Civil War had left widows and orphans back East, young ladies with good educations, superior morals, and plenty of backbone. All they needed was the knowledge of the need to come West. He could provide that knowledge. He could serve as Seattle’s Emigration Agent and bring home the brides.

Now, I will tell you, there are two schools of thought on Asa Mercer. There is no doubt the citizens of Seattle applauded his initiative. And after his first foray netted him about a dozen women, he was voted into the Washington State senate. But other contemporary sources are less kind, particularly when Mercer decided to take his adventure to a grand scale. He vowed to return to the East Coast and request a troop carrier from none other than President Lincoln, planning to bringing as many as 700 women to Seattle’s shores.

His dream immediately encountered challenges. Traveling took money, and the young professor had little. But dozens of bachelors in Seattle were willing to invest in his scheme so long as he brought them each back a bride of good repute. Some stories have it that Mercer accepted as much as $300 per bride, a goodly price in those days. Whatever the amount, he left Seattle with money in his pocket and the cheers of his comrades ringing in his ears. But his good fortune quickly evaporated.

As a child, Mercer had supposedly met Abraham Lincoln, and he was counting on his connection with the president to win him a decommissioned troop carrier left over from the Civil War as an inexpensive way to transport his bevvy of belles. He arrived in the capital to find it wreathed in black: Lincoln had been assassinated. The story goes that after being shunted from one government official to another, he ended up meeting with Ulysses S. Grant, who agreed that Mercer might have a ship, if he could purchase it.

The price requested was pennies on the dollar for the worth of the ship, but still far beyond Mercer’s means. Enter transportation magnate Ben Holladay, whose stage coaches had helped fuel the California Gold Rush. He offered to start a shipping company, buy the ship for Mercer and carry the party of 700 women back to Seattle for a pittance. Overjoyed, Mercer signed the offered contract and went back to recruiting among the towns between Boston and New York, which had lost not only men but manufacturing jobs because of the war.

He must have sung a good song, for ladies lined up to join his expedition. That is, until several prominent newspapers began questioning not only Mercer’s motives, but the motives of the women interested in going with him. Mercer, they insisted, was only gathering bits of muslin that would end up in dens of ill repute or married to brutish husbands who would all but enslave them if they weren’t scalped first. They called the women Sewing Machines, Petticoat Brigade, and a Cargo of Heifers. One editor firmly stated that any woman willing to go all the way across the country to find a husband didn’t deserve one. The flood of recruits dwindled to a trickle.

Even worse was the delay in sailing. Days turned into weeks and then months, and still the S.S. Continental wasn’t ready. Then Holladay asked Mercer for more money. It seemed the contract he’d signed stated that if the full complement of ladies was not ready to sail on time, the price for passage went up. Desperate, Mercer turned to families and then bachelors to try to fill out his order of passengers. While some women, it appears, had been promised free passage (paid for by Seattle’s bachelors), he demanded that others pay full fare and more. The money he’d been given in Seattle was spent to pay for hotel fees as everyone waited for the ship to set sail.

The good ship Continental finally left New York on January 16, 1866, with a complement of 100 passengers. Approximately 50 were ladies under the escort of Asa Mercer, Seattle’s Emigration Agent Extraordinaire. Most of the others were married couples, children of those couples or widowed mothers, or single men who had paid Mercer for the privilege of sailing to Seattle. One was none other than a reporter associated with the New York Times.

Roger Conant had come from a well-to-do family. He’d studied law and fought for the Union before becoming a reporter. But the information he sent back from the Continental are not the unbiased, analytical commentary one might expect. Conant delighted in looking for the salacious, the remarkable. He didn't have much use for Mercer and tended to poke fun of the ladies, calling them Fair Virgins and teasing them about their love life. Thanks to Conant's journal, published as Mercer’s Belles, and the journals of several of the ladies (such as Flora Pearson Engle), we know quite a bit about what befell Mercer’s maidens on that fateful journey.

And what an amazing journey it must have been! Remember that these women had rarely set foot outside their little villages. Now they were making call at exotic ports like festive Rio de Janeiro, the forlorn Straits of Magellan, and the wild Galapagos Islands. To make matters even more exciting, everywhere they went, men begged them to stay! The ship’s officers set up a round of flirtations, so determined to win the hands of their fair passengers that Mercer had to set up rules against dallying aboard ship. No one paid him the least mind. The military officers of Chile tried to appropriate them to teach there instead. And the good citizens of San Francisco offered them lucrative jobs and marriages to remain behind in the City by the Bay.

Mercer’s hands were full trying to keep his charges contained. Unfortunately, he had other problems, as his financial troubles hadn't ended in New York. Some would-be passengers were left behind, and they claimed he had bilked them out of their savings to finance his bride ship. One woman even sued him for selling her furniture to pay his bills. At one point, he asked several of the women to sign promissory notes, according to Conant, saying that their husbands would pay the price for them once they reached Seattle. And just when he must have thought he was nearly home free, Holladay pulled a fast one when they reached San Francisco, refusing to allow the Continental to continue on to Seattle.

Faced with the need to ferry his dwindling set of ladies north, Mercer wired to the Governor of Washington for funds. What came back was a telegram congratulating him on his accomplishments, but lamenting that the state coffers were empty. Mercer had to pay his last pennies just to read the refusal. The story goes that he sold some of the women’s goods to pay for their hotel bills before finding some lumber schooners whose captains were willing to carry the ladies to Seattle for the pleasure of their company.

Only when they reached Seattle did some of the women learn that Mercer had bartered for their lives. Conant claims that such stellar characters as men named Humbolt Jack, Lame Duck Bill, Whiskey Jim, White Pine Joe, Bob Tailed, and Yeke showed up demanding someone’s hand in marriage. When the ladies refused to so much as speak to them, the men vowed vengeance on Mercer. Other fellows were more practical about the matter. Conant tells of a stranger who arrived in town, claiming to have a farm far outside the city. He asked Mercer to provide him with two or three women to take back with him, so he could see which would be more suitable for his wife. None of the women agreed to accompany him. Imagine that!

Whether Mercer was a courageous fellow out to civilize the wilderness or a cunning charlatan out to gather his fortune, the legend of the Mercer belles has fascinated the people of the Northwest for generations. If you'd like to hear more of the stories about what happened on that fateful ship, try The Bride Ship, book 1 in my Frontier Bachelors series.

Doc Maynard, Father of Seattle or Its Biggest Scoundrel?

Doc Maynard was one of Seattle’s founding fathers, and, in my opinion, one of the most colorful. In 1852, David Swinson Maynard came to Seattle, before it was even a town, but his story starts on the other side of the country. After earning his medical degree and marrying a pretty lass named Lydia, he moved his young family to Cleveland, where he dabbled in business while running a medical school. Misfortunes in both made him decide to strike it rich in California, but he met two things along the way that would change his life.

The first was cholera. Everyone had it, and anyone who survived after his treatment was more than happy to pay him in food, animals, and funds. He’d never made so much money being a doctor before. The second was a widow of one of the men he unsuccessfully treated. Catherine Broshears was beautiful and sweet, and he decided to accompany her to Olympia in what was then Oregon Territory instead of the Gold Fields. Along the way the pair fell in love, but her brother refused them permission to marry. It may have been the fact that Maynard was so quick to fall into and out of fortunes. But it may have had more to do with the fact that her brother suspected that the divorce Maynard convinced the territorial legislature to grant him wasn’t strictly legal.

Either way, Doc relocated to the Seattle area. He started out paying the natives to package up wood and salmon to sell to folks in San Francisco, then used the proceeds to open a store. From there, he claimed a tract of land for himself and his wife before convincing Catherine’s brother to let him marry her. But that was just the beginning of Maynard’s influence on Seattle:

- He convinced the settlers to name the new town after his friend, Chief Sealth.

- He was the first Justice of the Peace in King County, and even studied law, being admitted to the bar in 1856.

- He is responsible for the odd angle of downtown Seattle streets, because he plotted the streets on his claim according to the compass points, while his neighbors insisted on following the line of the shore.

- He was one of Seattle’s first post masters, hosting the post office at his store (and guaranteeing he’d have regular shoppers).

- He sold his lots cheaply or gave them away to people he thought would be good for the city, such as Henry Yesler, who built the first sawmill on Puget Sound, and Lewis Wyckoff, a blacksmith and later one of Seattle’s first lawmen.

- He opened the first hospital in Seattle, an enterprise that failed because he insisted in treating whites and Native Americans alike, and he never demanded payment.

Perhaps one of the most famous stories about Maynard has to do with his wives. It seems that Lydia was never told of the divorce and wrote to him about her share of his acreage. Legalities being what they were, she had to come to Seattle to be part of any settlement. According to historian Murray Morgan, Doc went down to the shore to meet her when she came in on the ship. He told a friend, “You’re about to see something you’ve never seen before: a man out walking with a wife on each arm.”

Seattle gawked as Maynard did just that. Lydia stayed with him and Catherine for a while until the legal matters were settled. Sadly, because Maynard had not been married to Catherine at the time of filing, and Lydia had never lived on the claim as is required of a wife, he had to give up half his acreage.

Doc still went out in style. When he died in 1873, Seattle held the largest funeral for that time. And the stories of his exploits are still told with fondness around the shores of Puget Sound.

Doc plays a role as the heroine's employer in Would-Be Wilderness Wife, book 2 of the Frontier Bachelor series.

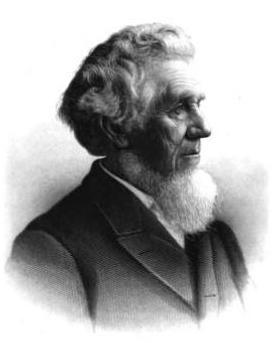

Daniel Bagley: Spiritual Father of Seattle

Daniel Bagley was born into a farming family in 1818 Pennsylvania, but he must have had an urge to wander from an early age, for he married when he was only 22 and promptly whisked his wife Susannah off to settle an Illinois prairie. He was ordained a Methodist minister in 1842 and took on the role of circuit preacher, riding all over the state. Ten years later, he was on a wagon train heading west to settle near Salem, Oregon. There he served as a missionary establishing churches.

Daniel Bagley was born into a farming family in 1818 Pennsylvania, but he must have had an urge to wander from an early age, for he married when he was only 22 and promptly whisked his wife Susannah off to settle an Illinois prairie. He was ordained a Methodist minister in 1842 and took on the role of circuit preacher, riding all over the state. Ten years later, he was on a wagon train heading west to settle near Salem, Oregon. There he served as a missionary establishing churches.

The legend goes that his wife’s health drove him north to seek the “clean air” of Puget Sound. I’m not entirely sure how Puget Sound is any cleaner than Salem at that point in history. Supposedly they came by horse-drawn buggy, but I’m finding that one difficult to believe since it appears there were no roads leading north from the Portland area to Seattle until much later than 1860, when Daniel and his wife and 17-year-old son Clarence arrived. However he reached Seattle, and whatever encouraged him to come, he started out as an agent of the American Tract society, passing out pamphlets to those who needed to repent, until he oversaw the building of what would become known as the Brown Church (as opposed to the only other church in town, which was painted white). Daniel was its first minister, preaching on Sundays and performing marriages, christenings, and baptisms for many of Seattle’s founding families.

And some of those marriages were memorable. One story goes that a young couple appeared before him, begging to be wed. Suspecting the young lady to be too young, he demanded to know her age.

"I’m over 18," she proudly proclaimed.

Unwilling to call her a liar, he married the pair. A short while later, her parents came pounding at his door, looking for their runaway daughter. It seems the couple had stopped first at the home of the irrepressible Doc Maynard, who had advised the girl to write the number 18 on two pieces of paper, then stick them inside her shoes. The thirteen-year-old was indeed standing “over 18” when she was married.

But much as his services were in demand, Daniel wasn’t content to minister only to the community's souls. He wanted to minister to their minds as well. He was one of the driving forces behind locating the territorial university (what would become the University of Washington)in Seattle . When the legislature was persuaded to make the offer, he encouraged local landowners to donate sufficient land to make the dream a reality. He also served as president on the university board of commissioners and appointed Asa Mercer as the first university president.

And it seems he supported young Asa in other ways. He had known Asa through Asa’s brother Thomas, who originally journeyed west in the same group as Daniel. Asa worked as a laborer to craft the first building for the fledgling university. But Asa too had a dream: bringing brides to wilderness bachelors.

As we’ve seen, there are two schools of thought on Mr. Mercer’s attempts to bring young ladies from the East to “civilize” Seattle. Some thought him a visionary; others a cunning confidence man. Either way, his second voyage was plagued with rumors of financial improprieties. When a number of the women refused to marry gentlemen who claimed to have paid for their passage, Seattle erupted in controversy.

Mercer hired the use of Yesler Hall (also known as the sawmill’s cookhouse) to make his case to the good citizens of Seattle. Daniel oversaw the meeting. Supposedly Mercer’s persuasive arguments and the backing of several of his lovely charges swayed Seattle to see things his way. Daniel later married Asa Mercer to Anne Stephens, one of the women he’d brought with him. Very likely Daniel officiated at more than one marriage of Mercer’s Belles.

But he didn’t stop his wanderings. He managed the Newcastle coal mines on the east side of Lake Washington for a time, then went back to circuit riding, preaching at a number of churches in the area. He died at age 87 and is buried beside his wife in Seattle. Their son Clarence went on to become one of the area’s earliest historians, penning multivolume histories of Seattle and King County, histories to which I owe much of the information in my Frontier Bachelors stories.

Daniel Bagley provides "encouragement" to my heroine in Frontier Engagement, book 3 in the Frontier Bachelors series. He will also play a key role in the upcoming Frontier Christmas Bride (title tentative), which will be published in December 2016.

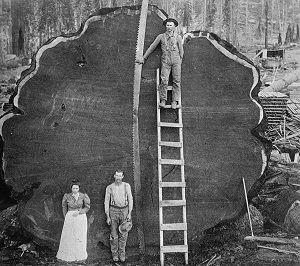

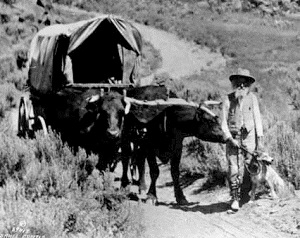

Ezra Meeker, King of the Oregon Trail

The Oregon Trail is a legend unto itself. Thousands of men, women, and children traversed the country to claim land on the West Coast. Ezra Meeker and his wife Eliza were among them. Ezra eventually settled in the Puyallup area south of Seattle, where his hop raising made him rich enough to build his wife a mansion that still stands today. He later lost all his money and tried to recoup it by selling supplies in the Klondike Gold Rush. But that’s not the most intriguing part of the story.

The Oregon Trail is a legend unto itself. Thousands of men, women, and children traversed the country to claim land on the West Coast. Ezra Meeker and his wife Eliza were among them. Ezra eventually settled in the Puyallup area south of Seattle, where his hop raising made him rich enough to build his wife a mansion that still stands today. He later lost all his money and tried to recoup it by selling supplies in the Klondike Gold Rush. But that’s not the most intriguing part of the story.

You see, when Ezra was up in years (70 to be exact, in 1900), he became concerned that people didn’t know or appreciate what the pioneers had accomplished in traveling the trail. Farmers were plowing over the land once crossed by wagon wheels, merchants were building businesses where campfires had kept away the night. He became obsessed with preserving the trail, wanting to see granite monuments erected all along the route. After careful planning, he decided to travel backwards along the trail, by ox-drawn covered wagon, to raise awareness and funds to purchase the markers. He set out in 1906 with his trusty oxen Dave and Twist, an amiable collie named Jim, and, eventually, a driver and cook named William Mardon, to speak about the trail and convince towns to place his markers.

The way wasn’t easy. Some towns refused to support him, unwilling to help an “old man” die out on the Plains or in the mountains. Twist did die along the way, and no other cow or ox would pull with Dave until Ezra lucked into a similarly sized ox named Dandy. When speaking fees failed to pay for his travels, he started selling postcards of pictures taken on the journey. Some towns put in markers while he was there; others put them in after he’d left.

It took him nearly two years to make it across the country, traveling beyond the start of the trail into Pennsylvania and New York. Though he was nearly arrested in New York City, he ended up getting his picture taken on Wall Street and driving across the Brooklyn Bridge. He then headed to Washington D.C. where his state congressional delegation had arranged a meeting with President Roosevelt, who was pleased to discuss Meeker’s vision. At that point, Meeker had earned enough money after his expenses to send the wagon and team home by boat and train, with only a few miles of pulling across land.

But that wasn’t his last trip along the trail. When Congress began discussing appropriating money for markers in 1910, Ezra spent another two years charting the path so the markers could be placed accurately. He continued promoting the trail at every major event along the Pacific Coast for another decade. When Dave and then Dandy passed away, he had them stuffed and donated them to the Washington State History Museum. He traveled the trail again by automobile in 1916 and met with President Wilson and again in 1924 by airplane and met with President Coolidge. In 1925, he spent some months driving an ox team for a wild west show. He even published a romance novel about the Oregon Trail. He was on his way once more along the trail, in an automobile designed for him by Henry Ford, when, in 1928, he died of pneumonia just short of his 98th birthday.

I grew up hearing stories of Ezra Meeker’s exploits. Every year in elementary school, we would tour the Washington History Museum and gaze in awe at Dave and Dandy. Although I understand the wagon is no longer strong enough for display, the valiant oxen remain standing, teaching new generations about the triumphs of the Oregon Trail.

I think Ezra Meeker would be pleased.

For more information on pioneer life in the Seattle area, see my Frontier Bachelors Series.