The Old One-Two: Boxing in Regency England

By Regina Scott

Boxing was easily one of Regency England's most popular spectator sports, enjoyed by kings and commoners alike. The men who taught it were called the emperors of pugilism, and those who practiced it were called the Fancy. At one match alone, over 200 thousand pounds were wagered on the outcome. It was not uncommon for twenty thousand people to view a match.

By far the most famous of the Regency era boxers was "Gentleman" John Jackson. Born in 1769 to a Worcestershire family of builders, John decided at age 19 to become a boxer, much against his parents' wishes. At 5 feet 11 inches tall and 195 pounds, his body was said to be so perfectly developed (with the Regency idea of "perfection" being the statues of the Greek gods), that artists and sculptors came from all around to use him as a model. He dressed well (although he favored bright colors) and spoke in cultured tones, making him the darling of the ton. His two flaws in looks, I learned, were that he had a sloping forehead and ears that stuck straight out from the sides of his head. Presumably, the sculptors and artists used someone else to model the head.

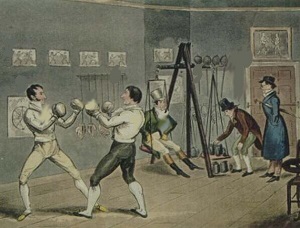

Although the acknowledged king of the ring, Jackson actually only fought professionally three times, losing once. However, as the other two times he fought men who were considered the top champions, he was considered in his time the heavy-weight champion of England. He is credited with a scientific style of boxing, which he taught three times a week during the London Season from his rooms in No. 13 Bond Street. Lord Byron was an avid student. This style included nimble footwork and the principle that a hit was not effective unless the distance was judged correctly. It also included adopting a posture of a slightly bent body, head and shoulders forward, and knees slightly bent and at ease with fists well up. He taught that fighting with the entire body (scrapping or bullying) was ineffective against the power of a well-trained fist, proving his point by having his students attempt to attack him and fending them off with fists alone.

He also is credited with keeping the sport honest in a time when bouts were often fixed. He developed the equivalent of the Boxing Commission in the Pugilistic Club, which collected subscriptions from wealthy patrons and sponsored fights several times a year. For each fight, a Banker was appointed to hold the purse as well as many side bets that might be made. Jackson was often nominated for this position.

He also is credited with keeping the sport honest in a time when bouts were often fixed. He developed the equivalent of the Boxing Commission in the Pugilistic Club, which collected subscriptions from wealthy patrons and sponsored fights several times a year. For each fight, a Banker was appointed to hold the purse as well as many side bets that might be made. Jackson was often nominated for this position.

Besides teaching and arranging fights, Jackson also arranged pugilistic demonstrations for the aristocracy, including fights before the Emperor of Russia, King of Prussia, the Prince of Wales, and the Prince of Mecklenburg. At the 1821 coronation of George IV, Jackson furnished a group of pugilists to act as guards to keep lesser mortals from attending the event. Other Regency era professional boxers were Tom Belcher, Tom Cribb, and Mendoza, the man whom Jackson beat to become champion.

A boxing match in Regency times was markedly different from what we know today. While practicing the sport was allowed, actual matches were frowned upon by the magistrates, and often had to be held out of town, sometimes in open fields. Instead of an elevated ring as we know it, an eight-foot square was roped off on the ground with stakes at each corner. Each fighter had a knee man and a bottle man, who also kept time on the rounds and breaks. The former knelt with one knee up for the boxer to sit on between rounds. The latter provided water for the boxer to drink, a sponge to wipe him down, and an orange to provide a quick burst of energy. Brandy was supposed to be used only for emergencies. A pair of umpires, usually former fighters themselves, kept the two fighters apart and agreed upon how to deal with questionable practices like holding a man’s hair to keep in him place to be hit. A referee was only used if the two umpires could not agree.

The bouts consisted of rounds; each round lasted until at least one of the men was knocked or thrown off his feet. A fight could last up to 50 rounds. If you do the math like I did, that means that someone was hit hard enough to fall down up to 50 times in one fight. And breaks between these rounds (after each hit) were only 30 seconds. In addition, bouts were fought with bare knuckles and bared chests. This was definitely not a sport for the squeamish!

Understandably, proper women were not supposed to attend boxing matches. However, some came in disguise and others less concerned with their reputations came openly. In addition, some women took boxing lessons in the privacy of their own homes. The practice was thought to provide an excellent exercise for young ladies, keeping them nimble and healthy. Apparently practicing was considered better than actually viewing the sport.

Near the end of the 19th century, improvements in the sport brought boxing closer to the sport we know today. Although boxing gloves were invented in the late 1700s, they were not required to be used until 1867, when the Marquess of Queensberry drew up rules of boxing. These rules also included shortening the rounds to a timed period, providing longer breaks between rounds, and limiting the kinds of blows that could count as a hit. During the Regency, however, boxing remained the no-holds-barred, no-quarter given kind of fight that made the aristocracy and the common folk cheer.

Be sure to read The Heiress Objective or Never Kneel to a Knight to see how it felt to take part in a boxing match.